Saskia Flament: «To ensure food safety, it is necessary to perform microbiological controls throughout the food chain».

Concepts such as ‘One Health’ or ‘From Farm to Fork’ are becoming increasingly relevant in the scientific, political and social landscape. Advocating global health that takes into account environmental, human and animal needs is not articulated as an option but as an indisputable necessity.

In the same way, providing food safety with a transversal character in which each link of the food chain is analysed and controlled makes it possible to advance towards fair, healthy and sustainable food systems.

As one of the main objects of study straddling these two strategies, we can place Escherichia coli, a bacterium that is part of the microbiota of our gastrointestinal tract and other mammals and that, on numerous occasions, can act as a pathogenic agent through the consumption of contaminated food.

In fact, a recent study published in the British medical journal The Lancet found that about 950,000 deaths in 2019 were attributed to E. coli. This is why its study, characterisation and control are critical to minimising its impact on public health and consolidating a safe food model.

D. in Health Sciences from the University of Santiago de Compostela, contract researcher at Campus Terra and member of the Reference Laboratory of Escherichia coli (LREC) of the USC; today we talk to Saskia Flament Simon about the characteristics that make E. coli such a relevant subject of study, the role of the strategy ‘From Farm to Fork’ and the problem of increasing bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

-There is a clear protagonist in your research work: Escherichia coli. What makes this bacterium such a relevant object of study?

-Escherichia coli is a bacterium with remarkable genetic variability, with commensal and pathogenic strains. This is due to the presence of certain genes that confer virulent characteristics and antibiotic resistance. In addition, this bacterium can cause intestinal and extraintestinal infections in humans and animals, and it is a very prevalent infectious agent causing zoonosis.

-In the same line, you are a member of USC’s Reference Laboratory of Escherichia coli (LREC). What role do these research groups play in fields of study such as yours?

-The Escherichia coli Reference Laboratory (LREC), directed by researcher Jorge Blanco, has extensive experience characterising pathogenic strains of E. coli. It has participated in food analysis within food safety and in the clinical diagnosis of human and animal biological samples when the causative agent is suspected to be E. coli. In addition, the LREC actively collaborates with the Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti (HULA) to investigate infections caused by E. coli in the population of Lugo. It is essential to have surveillance programs and epidemiological monitoring of these infections to establish appropriate preventive measures, especially given the alarming increase of multiresistant strains to antibiotics.

-Detecting E. coli in contaminated food and water is key to guarantee food safety. What are the latest advances in this area? What role does the development and use of kits for serotyping these bacteria play?

-Today, public databases contain an impressive number of fully sequenced bacterial genomes thanks to the development of new sequencing technologies. Undoubtedly, bioinformatics resources and artificial intelligence are protagonists in our field of research, as well as in others.

However, classical techniques such as serotyping, which makes it possible to identify the O and H antigens of E. coli, are still necessary for the initial characterisation of strains and even for the development of vaccines.

-Many animals in our environment are reservoirs for strains of this bacterium. How are these strains transmitted to humans? How can we intervene in the food chain to reduce E. coli contamination?

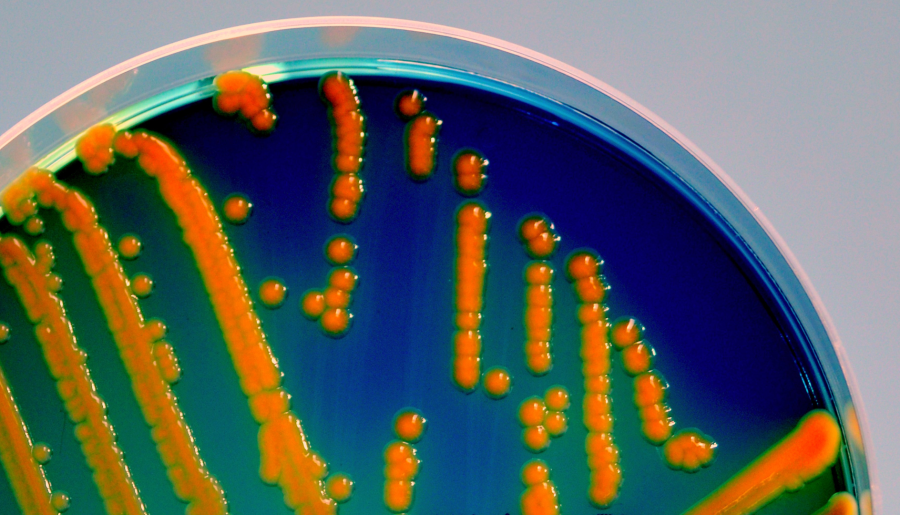

-Since E. coli is part of our gut microbiota and that of other mammals, the main source of infection is faecal contamination of the food we eat. Microbiological controls are necessary to ensure food safety along the entire food chain, understood in its broadest sense, i.e. “from farm to fork”.

-Antimicrobial resistance is undoubtedly a significant global public health challenge. Where are efforts to tackle this problem being focused?

-Given the magnitude of the problem, forces are joining forces globally to address it from a “one world, one health” perspective, recognising that antibiotic resistance affects global health and involves numerous sectors, such as human medicine, veterinary medicine, animal husbandry, agriculture and aquaculture.

Numerous bodies, including the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), are working together to coordinate different strategies. At the national level, we have the National Plan against Antibiotic Resistance (PRAN). The action plans include elaborating reports and recommendations for antibiotic consumption, monitoring the evolution of resistance in the bacterial population, and dissemination and research activities.

-You have stayed internationally at the Hôpital AP-HP Beaujon in France. What would you highlight from this experience? How important is this type of stay for you in the career of a professional researcher?

-From my stay at the Hôpital AP-HP Beaujon in Paris, under the direction of the researcher Marie-Hélène Nicolas-Chanoine, I would highlight the excellent treatment received and the valuable learning acquired since I was at the beginning of my predoctoral stage. In her research group, I had the opportunity to study biofilm formation in E. coli strains from patients with extraintestinal infections, which resulted in a joint publication.

Staying abroad and at the national level enriches a researcher’s career, as it allows them to learn new techniques and establish collaborations. In science, as in other fields, collaboration is very positive.